Created Date:

Last Modified:

The New Arrol-Johnston Car Co. Ltd.

Arrol-Johnston’s second car factory.

Location

Underwood Weaving Mills, Underwood Road, Paisley, PA3 1TQ.

Date

1901 – 1913.

-

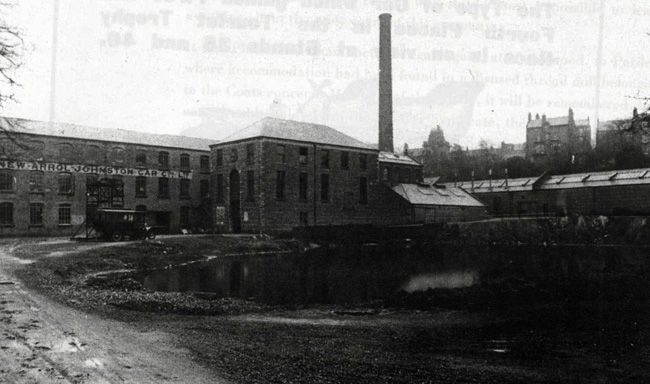

The Arrol-Johnston Underwood Works, Paisley, with the company's new name just visible

The Arrol-Johnston Underwood Works, Paisley, with the company's new name just visible -

A 1902 Arrol-Johnston Dogcart, © National Motor Museum, Beaulieu

A 1902 Arrol-Johnston Dogcart, © National Motor Museum, Beaulieu -

The 18 h.p Arrol-Johnston, 1906, © National Motor Museum, Beaulieu

The 18 h.p Arrol-Johnston, 1906, © National Motor Museum, Beaulieu -

The Arrol-Johnston “ice motor car” pictured before leaving for Antarctica. It had a 12-15 h.p air-cooled engine, with a pipe going from the exhaust under the footboard to act as a footwarmer, source: The Graphic, 26th October 1907

The Arrol-Johnston “ice motor car” pictured before leaving for Antarctica. It had a 12-15 h.p air-cooled engine, with a pipe going from the exhaust under the footboard to act as a footwarmer, source: The Graphic, 26th October 1907 -

1912 Arrol-Johnston 15.9, with a four-cylinder, 3.8-litre engine; this car is now on display at the Riverside Museum, Glasgow, source: BritainByCar

1912 Arrol-Johnston 15.9, with a four-cylinder, 3.8-litre engine; this car is now on display at the Riverside Museum, Glasgow, source: BritainByCar -

The Finishing Shop, inside the Underwood Works

The Finishing Shop, inside the Underwood Works

Commentary

On Thursday, 8th May 1901, fire completely destroyed the Arrol-Johnston works (still known as the Mo-Car Syndicate), at Camlachie, with the loss of all production, drawings and records.

Eight days later, the company announced that it would be resuming work at the vacant Underwood Thread Mill in Paisley, thanks to the owners, Archibald and Peter Coats, who were shareholders in the Mo-Car Syndicate. The factory was located in one of the of mills directly opposite St James's Church, but south of the railway.

However, car production did not get underway until the following spring; the loss of drawings in the fire meant that new patterns had to be made from existing cars.

For the next three years, Arrol-Johnston continued to build their trusty Dogcart. An article in ‘The Scotsman’ in February 1904, summed up the company and car as follows:

“They make no pretentious claims in the matter of speed, but aim rather at producing cars which can be relied upon to do their work under all conditions of road and weather”, adding “in external appearance the varnished walnut external body of the car forms a serviceable and agreeable contrast to the more gaudy productions.”

Although distinctly old-fashioned in appearance, the cars were mechanically unconventional. They were powered by a twin-cylinder underfloor horizontally-opposed engine, with its own patent magneto, automatic lubrication, and a four-speed gearbox.

By 1903, however, changes were beginning to take place. George Johnston became less prominent in running the factory and his role as chief engineer was taken over by John Stewart Napier. Sir William Beardmore – shipbuilder and engineer – became a major shareholder, and by the beginning of 1905 had gained complete control of the business. Under new management, the company name changed from the Mo-Car Syndicate to the New Arrol-Johnston Car Co. Ltd.

1905 also saw the introduction of three new models: the 12/15, 18, and 24/30 - all very different in appearance from the traditional dogcart, and much more akin to the then current styles.

The 18 h.p car, driven by John Napier, won the first Tourist Trophy Race – today, the oldest regularly run motor competition in the world. Organised by the Automobile Club, and run on the Isle of Man, the first Trial was designed as a competition for ‘touring’, as opposed ‘racing’ cars, with a view to increasing the general acceptability (and sales) of motor cars.

Although Arrol-Johnston had little further success in motor sport, they did achieve a certain amount of kudos through their connection with Ernest Shackleton’s 1907-1909 British Antarctic ‘Nimrod’ Expedition, aiming to be the first to reach both the South and South Magnetic Poles.

Choosing to rely on private sponsorship to finance his plans, Shackleton’s main sponsor was Sir William Beardmore, whose support included the provision of a specially designed expedition motor vehicle – made by Arrol-Johnston.

The vehicle itself did not really live up to expectations. The heavy wheels had no traction in the snow, and in the end its use was limited to ferrying supplies relatively short distances where the ice was smooth and hard.

Although Ernest Shackleton did not reach the South Pole (a team did, however, get to the Magnetic Pole), the expedition was not judged a failure. In appalling conditions the four-man party had reached 88° 23´ south, 97 miles from the Pole; further south than anyone had ever been. On his return to Britain, Shackleton was feted and showered with honours, and the car - despite its shortcomings – was described in glowing terms. The Daily Telegraph and Courier praised “the soundness and sturdiness of this Scotch (sic) car”, while the Preston Herald, linked Shackleton’s car to the rest of the Arrol-Johnston range, commenting, “a marvellous witness to the durability and workmanship put into these cars”.

In the spring of 1909, Thomas Pullinger was appointed general manager at Arrol-Johnston. Born in London in 1867, and educated at Dartford Grammar School, Thomas Pullinger was originally trained in bicycle manufacture before going on to work for Darracq, Sunbeam, and then Humber. In the early part of the century, he had frequently competed in a Beeston Humber against John Napier, driving an Arrol-Johnston. In November 1909, the factory suffered its second serious fire, with the destruction of the tool, paint, and trimming shops. However, this did not hamper the launch of the new 15.9 h.p Arrol-Johnston, two-and-a-half months later, at the Olympia Motor Show.

Commenting on the new car, the Daily Telegraph and Courier reported that T.C Pullinger “has given such a number of improvements that one almost shudders to inflict them on one’s readers.”

His appointment seems to have had an immediate and very positive effect on the company’s fortunes. The dynamism he brought to Arrol-Johnston showed itself in the introduction of new models, the standardisation of spare parts (an industry first), experiments with electric cars, and – perhaps most significantly – increased production.

It was this final development, and the limited space available in the Underwood factory, that led Arrol-Johnston to organise the construction of an entirely new factory, 80 miles to the south, just outside Dumfries, to which they moved in 1913.

With thanks to Dr Nina Baker for her help in the preparation of this article, women in engineering history blog.

Other locations

Camlachie, Strathclyde

Heathhall, Dumfries & Galloway

Springburn, Strathclyde

West Linton, Borders

Further details

• The Scottish Motor Industry, Michael Worthington Williams, Shire Publications Ltd, 1989.

• In the Driving Seat – a century of motoring in Scotland, Jack Webster, Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, 1996.

• History of the Motor Industry in Scotland, A Craig Macdonald and A S E Browning, Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 1961.

• Scottish Vehicles, Rod Ward, Zeteo, 2015.

• Lost Causes of Motoring, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, Cassell, 1960.